|

Fighters

for the King

Loyalists

fought in more than 150 military units that were raised during the

Revolutionary War. In the South alone, British military archives list

26 units that fought during southern campaigns.

Most

British Army regiments had long, well-documented, and respected

histories. Loyalist units, however, came and went, dissolving or

merging over the course of the war—and leaving scant records

behind. When the war ended, the British Army would live on,

while the Loyalist Provincial Corps, as the British called the Tory

units, would fade away.

The

following introduction to these nearly forgotten Loyalist military

units was contributed by Todd W. Braisted, director of the On-Line

Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies (see

http://www.royalprovincial.com/index.htm ) and a longtime

authority on the Provincial Corps. The On-Line

Institute was a major source for the unit descriptions, which were

written by Roger MacBride Allen and his father, Thomas B. Allen, the

author of Tories.

King George III

The

Loyalist equivalent of the Continental Army was referred to as the

Provincial Corps. Raised under the auspices of the commander in chief

of the British Army, in all theaters of the conflict, these troops

were enlisted for the duration of the war and liable for service

anywhere in North America. They received the same pay, provisions,

quality of clothing, arms, equipage, and accoutrements as British

soldiers, while serving under the same discipline. Some units were

short-lived and some served for the whole war.

Numerous

British officers and sergeants were sprinkled throughout these units

to help bring them up to a state of tactical proficiency and

professionalism. Provincial units were primarily used in limited

roles early in the war, but as the number of British units dwindled

in America, the value of the Provincial units increased, taking a

leading part, particularly in the South. When units became

significantly under-strength, with little prospect of recruiting

anew, members of those units were generally drafted into other

regiments.

Five

Provincial regiments received the special status of being placed on

what the British Army called the “American Establishment.”This

was considered an honor, given to units that had achieved their

recruiting goals or performed particularly well in battle. Not

coincidentally, current or former British officers commanded four of

these five units. Seven Provincial units, including three on the

American Establishment, achieved the highest recognition by being

placed upon the Regular Establishment.

Some

Loyalist units were raised by order of the governor of a province, if

the British government functioned there. These were standing corps,

paid for and supplied through the governor’s budget. These

units were not a part of the army per se, and did not enjoy the same

benefits of Provincial troops. Most served only a limited time and

all were disbanded before the end of the war. Such units included

the West Florida Provincials, the East Florida Rangers, and

the Ethiopian Regiment. These were the equivalent of the

so-called State Troops raised from time to time by the states.

Militia

laws were either in place or passed wherever the Crown held sway.

Under these laws, the militia generally consisted of all able-bodied

males between the ages of sixteen and sixty, usually with exemptions

for Quakers, firemen, and the civil authorities. These units were

typically raised along county lines and only served when needed. Some

of these militia corps were volunteers, while others were compulsory.

The volunteer units were often uniformed, while the other corps

mostly provided their own arms, ammunition, equipage, and clothing.

Militia

men on active service generally drew British provisions—and

sometimes British Army pay. This confirmed the rank of officers in

the army as well as guaranteed them half-pay upon retirement, known

in the British Army as “reduction.”

The

militias primarily acted on the orders of a province’s

governor, as in Georgia, Nova Scotia, and New York. British military

commanders took a much more active role in directing the activities

of militias in the Carolinas.

The least structured

units tended to be those under the appellation of “Associators”

or “Refugees.” These tended to be separate and distinct

from the army, tailoring their operations to achieve self-interests

or financial gains. One of them, the Associated Loyalists,

operated under a charter from the king himself. The Loyal

Associated Refugees not only lived by “interrupting

commerce” as privateers but also by contracting to perform such

work as collecting wood from inhabitants of Martha’s Vineyard.

These units received minimal support from the British, and their

near-autonomy was a source of some friction with different British

commanders.

The

following military units described here were more or less raised

through official means and were regularly supplied with men.

Temporary formations were often created as the exigency of the

situation required, such as temporary militia companies formed at

Savannah and Yorktown during their respective sieges. Militia units

were likewise occasionally formed by local army commanders in Georgia

and the Carolinas, and these units sometimes quickly passed into

history. The militias throughout the Province of Quebec were more

regularly organized, but they had scant active military roles.

A

large number of Loyalists served in both the Civil Branches of the

Army and Artillery. These organizations were the support services of

the military, employing wagoners, laborers, and skilled mechanics.

Thousands served in their ranks, in all theaters of the war.

A

few Loyalists, such as Oliver DeLancey, Jr., and Arent Schuyler

DePeyster, were officers or enlisted soldiers in Regular British

regiments. More served in the Royal Navy, some by voluntary

enlistment, others the results of impressment. Thousands

additionally took to the seas in privately owned and armed warships,

known as letters of marque or privateers. These ships, usually built

for speed over heavy firepower, were engaged in attacks on enemy

commerce, with the prize vessels and cargoes sold for the benefit of

both the owners and crew.

Loyalists

willing to risk their lives served as spies, army guides, or ship

pilots. The Indian Department employed many Loyalists and

occasionally had in it such units as Brant’s Volunteers

or the Loyal Foresters.

One

of the most distinguished and prominent Loyalist units, made up

mostly of New Yorkers, was the King’s American Regiment,

led by Colonel Edmund Fanning. The regiment served in six major

campaigns across the length of the eastern seaboard. The officers and

men fought in some of the bloodiest battles of the war, ending their

service by being placed on the regular British Establishment, an

honor bestowed on but a handful of Loyalist units.

–Todd

Braisted

Private (left) and

officer in the King’s American Regiment

Loyalist

Collection, University of New Brunswick, Canada

The Armed Loyalists

These

descriptions of Loyalist military units in many ways reflect the

complicated history of the units themselves. Records are spotty,

primarily because the British Army, a great keeper of records, did

not regard their Loyalist comrades as equals. The Crown did not award

battle honors to British regiments that fought in America because the

British saw the Revolution as a civil war. (Battle honors were,

however, awarded for actions against America’s French and

Spanish allies in the West Indies and other theatres.)

More than 1,500 Americans became Loyalist officers. Their success at

recruiting produced unexpected results. Regular British Army

officers, whose commissions almost inevitably stemmed from wealth and

family connections, resented the Loyalist officers’ easily

acquired commissions and promotions.

The better the Loyalist officers were at talking and promising, the

quicker they formed regiments and the faster came their captaincies

and colonelcies. Regiments were formed not on the basis of military

wisdom or experience but also on the ability of recruiters to get men

to sign up for specific periods of time. Regulars, as professional

officers, kept track of their careers, not their calendars.

A

number of units came and went. They usually consisted of twenty or

even fewer men who were assigned to garrison duty, police patrols,

digging fortifications, cutting wood, guarding woodcutting parties,

and other routine duties. They left behind little record of what they

had done. Many of these smaller units were eventually merged into

larger units, often were called “Independent Corps” or

“Independent Companies.” But many smaller units did see

significant combat and fought valiantly.

Adding

to the confusion, many units were known by more than one name–or

even two or three similar names. A unit’s name was not always a

reliable guide to where the unit was raised. For example, the Jamaica

Corps was raised in New York and Charleston. Many units were raised

in one locale and transported to another. The Maryland Loyalists, for

example, fought in Florida, were all taken prisoner and shipped to

Cuba (a possession of Spain, which had joined France as an American

ally). From Cuba, the Marylanders went to New York. At the end of

war, while sailing for Canada, most of them died in a shipwreck.

Several

units recruited free blacks and escaped slaves who were offered their

freedom in exchange for serving the Loyalist cause. Officers of such

units were white, but the ranks of some included whites. These units

did some fighting, but more typically served as “Pioneers,”

a term that in this context means doing the digging, cleaning, and

other less glamorous military tasks.

Many

reports describe the drafting of one unit into another. In effect,

this meant that the unit was disbanded, with its soldiers and

officers being placed in the receiving unit. A unit might even be

drafted into two or more receiving units. This might happen if morale

had collapsed in a unit, if the unit had simply lost too many men to

disease, war wounds, and desertion, or if, from an administrative

point of view, the unit was simply too small to bother with.

Little

can be found about some units, but sometimes information about

someone connected to the unit can illustrate some aspect of

American-versus-American warfare. Units for which little is known

except the unit names and commanders, and those not

known to be involved in military actions connected to the American

Revolution have been included in the list for the sake of

completeness, and for the convenient reference of future researchers.

They are listed separately.

–Roger MacBride Allen and Thomas B. Allen

----

Adams Company of Rangers

An independent company raised for the

British Army, this unit was founded by Samuel Adams, who lived in

what is now Arlington, Vermont. Rebels once hoisted Adams, in an

armchair, twenty-five feet to place him next to a stuffed catamount

on a tavern sign pole in Bennington. Most of the unit’s 70 men

came from the New Hampshire Grants, the long-disputed territory that

became Vermont. The men worked as guides, carried messages between

commanders, and stole cattle from Rebel farms during General

Burgoyne’s invasion of New York. After the defeat of Burgoyne

at Saratoga, Adams fled to Canada, a flight probably also taken by

his men, who faced Rebel retaliation if they returned home.

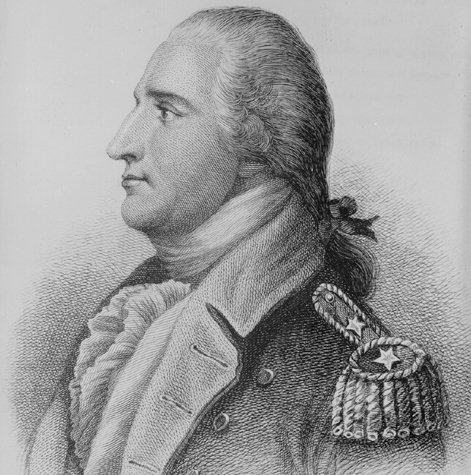

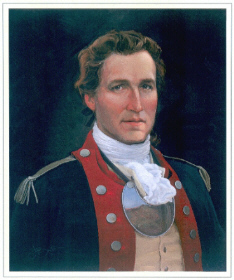

American Legion

Raised by Benedict

Arnold, the Legion included many deserters from the Continental Army.

In December 1780, the Legion, along with Hessians and British regular

troops, invaded Virginia by sea, raiding, burning, and looting

Richmond and wrecking a cannon foundry. The Legion raided the area

again in spring 1781 and in September 1781 attacked New London,

Connecticut, and nearby Fort Griswold. One of 212 men in the unit was

a Patriot mole whose never-accomplished goal was to kidnap Arnold and

bring him through the lines to be hanged as a traitor.

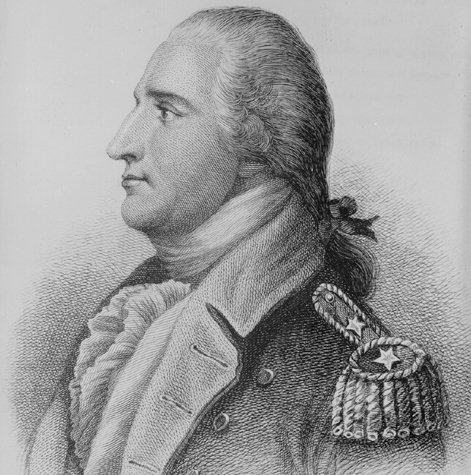

Benedict Arnold in the uniform of a

Continental Army major general.

Drawn

by Pierre Du Simitiere, New-York Historical Society.

American

Volunteers (also known as Ferguson’s Provincials)

were Loyalists trained, fed, and paid as if they were in the regular

British Army. The unit was initially formed of

175 New York Tories who

served as riflemen and rangers under Lieutenant

Colonel Patrick Ferguson of the British Army. Active in

the siege of Charleston, they also fought at Monck’s Corner,

South Carolina. While serving in the South, the Provincials helped to

train other Loyalist regiments. The Volunteers formed the core of the

1,000-man force that was nearly wiped out in the battle of King’s

Mountain on October 7, 1780.

Patrick Ferguson

Anonymous

miniature, c. 1774-77, from a private collection

Armed Boat Company

Authorized by General Sir Henry Clinton

in July 1781, this seagoing unit manned armed whaleboats (narrow

vessels about thirty-six feet long, with pointed bows and sterns,

sometimes armed with small cannon). Several members of the unit were

former slaves. Among the unit’s combat operations were attacks

on Rebel whaleboats in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in January 1782 and

an attack on a Rebel blockhouse at Tom’s River, New Jersey, in

March 1782. The company’s first commander, William Luce, was

almost immediately captured by the Rebels. His successor, Edward

Vaughn Dongen, enlisted more than 125 men, mostly from Essex County.

Artificer and

Labourer Volunteers

One of three units

raised by Captain Robert Pringle, an officer in the Royal Corps of

Engineers. He was in charge of constructing new defenses in the

harbor of St. John’s, Newfoundland, when the war began. This

unit was about 120 strong. See Newfoundland Regiment.

Associated Loyalists

A ferocious Tory

guerrilla organization, it was overseen by a Board of Directors that

included its founder and real commander, William Franklin, last Royal

Governor of New Jersey and son of Benjamin Franklin. The Associates

staged raids across Long Island Sound to Connecticut and were

involved in the notorious hanging of a New Jersey Rebel, Captain

Joshua Huddy. Franklin also raised the King’s Militia

Volunteers, whose chores included cutting wood for the British Army.

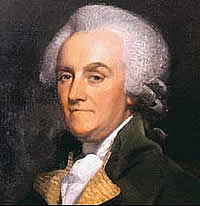

William Franklin

Detail

of 1790 portrait by Mather Brown

Bagaduce

Regiment

Before the Revolution

began, Thomas Goldthwait, a Boston merchant, served as Secretary of

War for Massachusetts Bay. He was also commander of Fort Pownall,

built in 1760 at the mouth of the Penobscot River (now in Maine, then

part of Massachusetts). When British

forces seized the fort’s cannons and powder in 1775, Goldthwait

was branded a traitor. As an admitted Tory, he formed and commanded

the Bagadue Regiment, named after a town later named Castine. He

later fled to British-occupied New York City on a Royal Navy warship

and eventually sailed to England, where he died in 1799. The

so-called regiment apparently was one of two battalions (the other

being from Boston) that combined to form the Massachusetts Militia.

Barbadian Rangers

Raised in Barbados from

July 1781 and intended for service in the Leeward Islands, the

Rangers were commanded by Captain

Timothy Thornhill, a member of what was called the

Barbados aristocracy of sugar and slaves. After fewer than 60

volunteers had been enlisted, a futile attempt was made to transfer

the unit to St. Lucia in hopes of finding more recruits there.

Bay Fusiliers (also

known as Mosquito Shore Volunteers and Black River

Volunteers)

Both free men and

slaves belonged to this unit, raised and based on the Mosquito Coast

of what is now Nicaragua and commanded by a British officer, Major

James Lawrie. The Fusiliers were used in operations

against forces of Spain, which had become an ally of the United

States after France’s entry into the war.

Black Dragoons (also

known as Black Pioneer Troop)

This unit, the only

troop of ex-slaves formed in South Carolina, initially had 71 men.

They would be among the very last Loyalists to be evacuated from New

York City in 1783.

Black Hussars (also

known as Deimar’s Hussars)

This unit of

black-coated troops were formed mainly of escaped German prisoners of

war who had been captured in the battle at Saratoga. Because they

were technically not prisoners but unarmed under a “convention”

of the British surrender, their status was hazy. Treated as

non-British but loyal, the hussars were commanded by Captain

Frederick von Deimar. They were attached at times to

Tarleton’s Legion and the Queen’s Rangers.

They served in the New York area, joined Loyalist raiders in New

Jersey, and patrolled the Long Island coast against raids from New

England whaleboats.

Black Pioneers

General Henry Clinton

formed this unit during his expedition to North Carolina. The initial

unit consisted of 71 escaped slaves, who were given their freedom.

They dug latrines, cleared ground to build camps, and did other such

menial army chores. Although no Black Pioneer was killed in battle,

many died of disease and overwork. New enlistments usually kept the

size of the unit to no more than 50 to 60 men. The Black Pioneers

were the only Loyalist unit to accompany Clinton in his attack on

Newport, Rhode Island in December 1776. After returning to New York,

the Black Pioneers in 1778 were sent to Philadelphia, where they were

ordered to “Attend the Scavangers, Assist in Cleaning the

Streets & Removing all Newsiances being threwn into the Streets.”

A second unit, which never got larger than 20 men, was disbanded in

1778. Another unit of Black Pioneers was raised during the

siege of Savannah in September-October 1779. Black Pioneers would be

among the last Loyalists to be evacuated from New York City in 1783.

The men received free land grants in Canada, but their land was

inferior to what was given to white Loyalists. One of the Pioneers’

commanders was Captain Allan Stewart of North Carolina, who would

later command the North Carolina Highlanders.

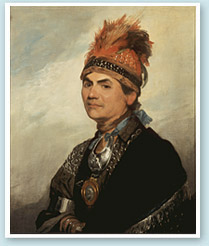

Brant’s

Volunteers

A powerful

raiding force of Indians and Tories, formed and led by Joseph Brant

(Thayendanegea), a Mohawk who was a close ally of Sir William

Johnson, the British superintendent of the northern Indians of

America. Brant’s Volunteers raided Rebel

communities and isolated Rebel farms in the Mohawk Valley and along

the New York frontier. They were unusual Tory guerrillas, for they

were not recognized officially and they were sustained by Brant’s

funds and their own looting. Eventually, however, Sir Frederick

Haldimand, governor of the Province

of Quebec and supervisor of frontier

military operations, gave them support. Because

of the unit’s lack of recognition (and British Army pay), many

members transferred to Butler’s

Rangers or other organizations.

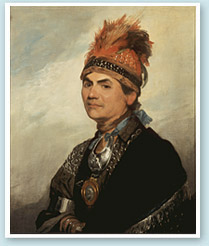

Joseph Brant

was painted by Gilbert Stuart in

1786 when he was in London

Collection

of the Duke of Northumberland.

British

Legion (also known as 5th American Regiment and Tarleton’s

Legion) was formed in 1778 by merging Philadelphia Light

Dragoons, Caledonian Volunteers, and Kinloch’s Light

Dragoons, a small unit raised near Jamaica, Long Island,

under the command of Captain

David Kinloch. In 1780 the unit absorbed the Bucks

County Light Dragoons. Most of the units’ troops

came from Pennsylvania and New Jersey. They fought in battles in the

Southern campaign at Monck’s Corner, Waxhaws, Fishing Creek,

Cowpens, Guilford Courthouse, Warwick Courthouse, and

Charlottesville. Survivors later merged into the King’s

Americans Dragoons. One of the Legion’s commanders was

Lieutenant Colonel Banastre

Tarleton, a brilliant British Army career officer who,

early in the war, captured Continental Army General Charles Lee.

Colonel Banastre

Tarleton, in a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, stands on Rebel

battle flags heaped at this feet. On Flag Day 2006 an

anonymous bidder paid nearly $17.4 million on for four rare flags

from the American Revolution. A flag he captured at Pound Ridge, New

York, is one of the first to display the 13 red and white stripes and

a flag he captured in South Carolina is one of the first to display

13 five-pointed stars on a field of blue.

National

Gallery, London

Bucks County Light

Dragoons, also known as Bucks County Dragoons

Raised in Philadelphia

in February 1778, the unit was sent to New York in 1778 and attached

to the Queen’s Rangers for the 1779 campaign, to the

British Legion for the 1780 campaign, and was permanently

merged into the British Legion in 1782. Lieutenant

Colonel John Watson Tadswell Watson, a British

Army officer from the elite Brigade of Guards, led the dragoons after

the regular commander, Captain Thomas Sandford, was taken prisoner.

Bucks County

Volunteers

Raised in the spring of

1778 under Captain William

Thomas, the unit may have had as few as 15 to 20 men at

times and was often attached to the Queen’s Rangers.

Butler’s

Rangers

Raiders with a

reputation for cruelty, the Rangers were raised by Lieutenant Colonel

John Butler of the British Indian Department in September 1777. In

one of its most notorious raids, about 200 Rangers and 300 Indians

raided Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania, in June 1778. They continued to

raid the New York frontier throughout the war. During a raid into

Cherry Valley, New York, Butler’s Indian allies killed unarmed

men, women and children. John Butler and his

son Walter kept the New York-Pennsylvania border dwellers living in

fear.

One company was sent to Detroit and raided Rebel

settlements along the western frontier. In the final Ranger action of

the war, one company raided and torched Wheeling in today’s

West Virginia. During their peak years the Rangers mustered more than

500 men. By the end of the war, more than 900 men had served in the

Rangers.

John Butler

Caledonian

Volunteers

Raised in Philadelphia

1777-78, the unit was merged with the British Legion in 1778.

The commander was Lieutenant

Colonel William Sutherland, who was with the British

soldiers at the North

Bridge in Concord when “the shot heard

round the world” began the Revolutionary War.

Canadian Companies

Canadian

referred to French-speaking Canadians, who were reluctant to get

involved in the fight between the British and the Americans. British

officers raising the units announced that two married men would be

pressed into service for every unmarried deserter. The 1st company

was raised from the Trois-Rivières district, the 2nd company

from around Montreal, the 3rd from Quebec. The 1st company served at

the failed siege of Fort Stanwix, New York, during the Burgoyne

invasion. The 2nd and 3rd marched with Burgoyne and were part of the

“Convention Army” that surrendered at Saratoga. Company

officers were Captain Samuel

Mackay, Captain Jean-Baptiste-Melchior Hertel De Rouville, Captain

David Monin, Lieutenant Jean-Baptiste Beaubien, and Captain

René-Amable Boucher de Boucherville.

Carolina Black

Corps, also known as Carolina Corps, Black Carolina Corps,

Black Corps of Dragoons Pioneers and Artifcers

This black unit was

raised as the British Army was leaving Charleston in December 1782.

After the Revolution, the corps of former slaves, amalgamated into a

single unit called the Black Carolina Corps, served in British

Caribbean possessions, which were slave states until slavery

was officially abolished in most of the British

Empire.

Charlestown

Volunteer Battalion

Created when the

British took Charleston, this battalion of volunteers from Charleston

assisted the city’s garrison. It was disbanded around the time

that the British evacuated Charleston in December 1782.

Detroit Volunteers

Raised at Detroit In 1777, the 47-man

company in late 1778 garrisoned Fort Sackville at Vincennes (in what

would become Indiana). The Volunteers’ history ended with the

fall of the fort to Colonel George Rogers Clark’s force in

February 1779, essentially ending British power in the region.

George Rogers Clark

Rogers

Clark Chapter, Ohio Society,

Sons

of the American Revolution

Duke of Cumberland’s

Regiment, also known as Montagu’s Corps.

A regiment former Rebel

prisoners who, after Spain’s entry into the war, agreed to

fight for the British—but only against the Spanish. Most of the

prisoners had been captured after the Continental Army’s

defeats at Charleston and Camden, South Carolina. In February 1781,

Charles Greville Lord Montagu,

last royal governor of

South Carolina, went on board prison ships in Charleston

and recruited hundreds of captives after promising they would not

have to fight fellow Americans. He commanded the regiment, which

initially had 500 men. A second battalion of about 100 men was raised

in New York. In August 1781 the regiment sailed to Jamaica, where it

remained for the rest of the war. After the war, many of Montagu’s

men went with him to Canada, where they were given grants of land.

Dunlop’s

Corps

This mounted infantry

and cavalry unit was based at Ninety Six, South Carolina, in December

1780. Major James Dunlop of the Queen’s Rangers, a

veteran of the battle of Brandywine and Ranger raids in New York and

New Jersey, was given temporary command of what then became known as

Dunlop’s Corps. Twice wounded in South Carolina battles, in

March 1781 Dunlop was wounded again and captured when his 180-man

corps was defeated in a skirmish at Beattie’s Mill. Fellow

Loyalists claimed that he was shot to death while being held

prisoner. His unit was disbanded in July 1781.

Emmerick’s

Chasseurs

Captain Andreas

Emmerick, a German officer serving with British forces, organized the

Chasseurs in August 1777. He selected 100 active “marksmen”

to be drawn from Loyalist units at Kingsbridge, New York, along with

50 men probably used for bayonet support. The corps fought in New

York battles and in 1778 was expanded and organized as two troops of

light dragoons, one light infantry company, one rifle company, and

three chasseur companies. The Chasseurs fought in many skirmishes in

the so-called “Neutral Ground” of New Jersey. Mutinous

officers lost confidence in Emmerick, creating discipline problems

that led to the disbanding of the unit; its men were drafted into

other regiments. In 1809, back in Germany, Emmerick joined an

insurrection against Napoleon’s occupation of Hesse-Kassel. At

the age of 72 he was executed by a firing squad.

Ethiopian Regiment

John Murray, Earl of

Dunmore, last royal governor of Virginia, created this unit of

ex-slaves. In November 1775 Dunmore issued a proclamation promising

freedom to slaves who took up arms for the British. Several hundred

slaves fled their masters and accepted his offer. From them he formed

a regiment and issued uniforms embroidered with the words “Liberty

to Slaves.” After Dunmore’s defeat at Great Bridge,

Virginia, in December 1775, the regiment was involved in the

evacuation of Norfolk and served British forces in the Chesapeake

area. Diminished by smallpox and other diseases, the Regiment sailed

to British-occupied New York and was officially disbanded. But many

survivors remained in British service. They were among the more than

3,000 former slaves who migrated to Canada after the war. The

commander of the regiment, Major

Thomas Taylor Byrd, was

the brother of a Rebel, Francis Byrd.

Florida

Loyalist Military Units

Florida

has been called the “14th

colony” and the only one that did not declare independence from

Britain. In the 1763 treaty ending the

French and Indian War, Britain received the Spanish colony of Florida

and part of the French colony of Louisiana. The British made the new

acquisition into two colonies: East Florida

capital, with St. Augustine its capital and

consisting of most of present-day Florida; and West Florida on

the north shore of the Gulf

of Mexico with its capital Pensacola. West

Florida was bounded by the Mississippi River

and Lake Pontchartrain in the west by the 31st parallel on the north

and the Apalachicola River on the east. Loyalists

fought Spanish rule in both colonies.

East

Florida Militia. 1st Regiment

formed into eight companies but never properly mustered. Attempts

were also made to recruit four companies of former slaves. A 2nd

Regiment was later formed. Records are scanty.

East

Florida Rangers (see also

King's Carolina Rangers). Raised

along the Georgia-Florida border and consisting primarily of East

Florida Tories, the Rangers served in their colony, joined in the

defense of Savannah in 1778, and, with Indian allies, staged

harassment raids along the Georgia frontiers, fighting in the battles

of Kettle Creek and Briar Creek. As the King’s

Rangers, the unit garrisoned Augusta. The

Rangers, using a dismantled church for raw materials, built Fort

Cornwallis to defend Augusta. They merged with Georgia Loyalists in

June 1782. Under their commander, Lieutenant

Colonel Thomas Brown, they fought savagely. (Brown was nicknamed

Burnfoot by Rebels whose fiery torture cost him two toes.) After the

fall of Georgia, Brown and many

Rangers joined thousands of refugees in flight to East Florida, still

in British hands. When that province was returned to Spain in the

1783 peace treaty that ended the Revolutionary War, Brown and his

Ranger refugees settled on Abaco Island in the Bahamas.

East

Florida Volunteers may be

another name for the East Florida Rangers or a name that singled out

volunteers who were drafted into the Rangers.

Natchez

Volunteers

Retired

British officers, seeking to aid Major General John Campbell,

commander of British forces in West Florida colony, raised this unit,

which included a motley crew of Tories who called themselves the West

Florida Independent Rangers. Learning of

Spanish plans to attack Campbell at Pensacola, the capital of West

Florida, they gathered volunteers, including Indians, to create a

diversion at Natchez (in present-day Mississippi), site of a former

British outpost, Fort Panmure. On April 22, 1781, the Spanish

garrison fled the fort, believing that the Natchez Volunteers, under

Captain John Blommart, had undermined it with explosives. In June

1781, after the Spanish defeated the British at Pensacola, they

retook the fort, and captured Loyalists who were there, ending the

service of the Natchez Volunteers. (See also West

Florida Independent Rangers)

West

Florida Independent Rangers, led by Captain

Thaddeus Lyman of Bayou Pierre, Louisiana, became involved with the

Natchez Volunteers (see).

The short-lived ranger unit joined in

an attempt to take Fort Panmure, a former British outpost, seized by

Spanish troops during their invasion of the British colony of West

Florida. In the aftermath of the failed operation, a party of about

100 refugees fled, traveling, on foot and on horse, from Natchez to

Savannah Georgia in 149 days.

West

Florida Loyal Refugees (displaced Tories

called themselves Refugees) were raised at

Pensacola in 1777 as a cavalry corps of two companies. The unit was

initially used to suppress Rebels’ illicit rum trade in the

Mobile Bay area. The unit surrendered to Spanish invaders in June

1780.

West

Florida Provincials (another name for

Loyalists) went into service with about 67

enlisted men and 17 officers. Between March and November 1778

Lieutenant

Colonel John McGillivray led

an expedition against Rebels,

journeying from Mobile to Natchez to Manchac and back return.

West

Florida Royal Foresters, raised

in mid-1780, fought the Spanish force that invaded the colony and

took what are today’s Mobile and Daphne,

Alabama. In January 1781 they joined British troops in a failed

attempt to retake the towns. They also helped defend

Pensacola in July 1781and were taken to Havana as Spanish prisoners.

By the time they were repatriated to New York, there were only two

officers, one sergeant, and ten enlisted men. The unit was disbanded

in August 1782.

Forshner’s

Independent Company

A small unit operating

in the “Neutral Ground” of New Jersey. Little is known

about its missions. One of few reports tells how Andrew Forshner and

two recruits crossed from Staten Island to New Jersey. After repeated

narrow escapes from American patrols, one recruit was captured.

Forshner and the other recruit managed to contact local Loyalists and

gather detailed intelligence before stealing a canoe and paddling it

back to Staten Island.

Garrison Battalion

(also known as Royal Garrison Battalion or Royal

Garrison Battalion of Veterans)

The unit was formed in

New York City in October 1778 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel

William

Sutherland of

the British Army and sent to Bermuda to defend against a French or

American attack that never happened. The British feared that

pro-American Bermudians would aid invaders. (Sutherland earlier had

been commander of the Caledonian Volunteers.) Reinforcements

arrived with Lieutenant Colonel Robert Donkin in 1779. Most of the

men in the battalion were British Army veterans and recovering

invalids.

Georgia

Loyalist Military Units

Georgia,

the only colony to be fall to the British during the Revolution,

fostered several Loyalist military units with many British and

American commanders.

Georgia

Artillery was raised in

Savannah by Alexander McGoun. He had been named by the Rebels’

Council of Safety in Georgia as a person “whose going at large

is dangerous to the liberties of America.” The Rebels later

confiscated his property, along with the property of 224 others named

by the Council.

Georgia

Light Dragoons consisted of Scot soldiers of

the British Army’s 71st Highlanders and Loyalists. Another

unit, known as the militia element of the Georgia Light Dragoons,

fought in several battles in Georgia. Reports of a unit known as East

Florida Volunteers may refer to the Georgia

Dragoons. Actions involving the two units overlapped and both appear

to have been present at some of the same events.

Georgia

Loyalists was raised

in Georgia in 1779 and sent to Charleston in December 1779. The unit,

which mustered only 72 men, merged with the East

Florida Rangers in June 1782 and was sent to

New York, where it was disbanded.

Georgia

Militia, under the command of Lieutenant

Colonel James Grierson of Augusta, gained a reputation as ruthless

foes. Grierson was singled out particularly for following British

orders to execute Rebels who broke their oath of loyalty to the king.

Rebels took Grierson prisoner in Augusta on June 5, 1781. He died two

days later, reportedly murdered in vengeance for his deeds.

Volunteers

of Augusta was a cavalry unit

formed of Loyalists who called themselves

Augusta Refugees. A song composed for the Volunteers included the

words The Rebels they

murder, Revenge is the word/Let each lad return with blood on his

sword.

Under the

command of Captain

James Ingram, they fought in a small,

inconclusive battle along Ogeechee River in May 1782.

1781-1782

Governor Wentworth’s

Volunteers

John Wentworth,

governor of the New Hampshire Grants (later Vermont) raised this unit

in 1776 to defend himself and his realm. He gathered about 20 men,

all certified as respectable and well-educated Loyalists, around him

and then he and the Volunteers fled to British-held Long Island,

where its first muster was taken. By the summer of 1778, the

Volunteers numbered 26. They are next heard from in March 1779 when

they joined other Loyalist forces in British-occupied Newport, Rhode

Island. They were later incorporated into the King’s

American Dragoons.

Guides &

Pioneers

Raised in New York in

1776 and attached to the Loyal American Regiment, the unit

served in 1781 in the siege of Charleston and in a raid into

Virginia. Beverley Robinson of New York, a wealthy Loyalist, raised

this unit and the Loyal American Regiment. He also played a role in

the treason of Benedict Arnold. Other commanders included Captain

Andreas Emmerick (see Emmerick’s Chasseurs);

Major Samuel Holland, former

royal surveyor-general of northern colonies; and Major John

Aldington, who enabled British invaders to make a surprise invasion

of New Jersey in November 1776 by leading them up a steep, narrow

path of the Palisades,

Guides &

Pioneers (Southern)

About a company or more

of these men, under Major Daniel

Manson, were regularly with Cornwallis’

army in the South. Small units probably assisted in the construction

or strengthening of fortifications and in the building and repairing

of bridges and boats.

Harkimer’s

Batteaux Company

Batteaux were mid-sized

boats used for various tasks. Captain Jost Harkimer’s batteaux

were used as transport during Colonel Barry

St. Leger's unsuccessful

Mohawk Valley campaign, which was part of Burgoyne’s 1777

invasion of New York from Canada.

Howetson’s

Corps

Lieutenant

Colonel James Hewetson, a retired British Army officer, formed the

unit, which initially had 171 men. The corps fought in a

skirmish near Livingston Manor in May 1777. Afterward, Rebels hanged

Hewetson (also spelled Howetson and Huston) for

recruiting Loyalists.

Jamaica Independent

Companies

Formed at Bluefields in

what is now Belize from survivors of various Jamaica and Mosquito

Coast units, it may have been merged into Odell’s Loyal

American Rangers.

Jamaica Corps (also

known as Amherst’s Corps)

Despite its name, the

unit was raised in 1780 in New York and in Charleston. In April 1783

it was amalgamated into the Duke of Cumberland’s Regiment

and Odell’s Loyal American Rangers. The unit’s

secondary name honored Jeffrey Amherst, a hero of the French and

Indian War. Amherst declined command of British forces in North

America and took no part in the Revolutionary War.

Jeffrey Amherst

Joshua

Reynolds, 1765

Jamaica

Loyalist Military Units

In

1655, the British captured Jamaica and used the plantation

slavery of Jamaica to launch the triangular trade: England’s

manufactured goods, Africa’s slaves, and the Caribbean’s

sugar. When Spain entered the Revolutionary War as an American ally,

Britain needed to protect Jamaica. And Loyalist troops, expecting to

serve in America, found themselves in a hot, fever-stalked outpost of

the British Empire.

Jamaica

Legion was raised in

Jamaica in late 1779. “Mostly composed of sailors,” the

Legion numbered about 210 men. It was sent to Nicaragua in February

1780. Ravaged by fever, the Legion in October 1780 was incorporated

into the Jamaica Volunteers.

Jamaica

Light Dragoons was raised

in July 1780 in Jamaica and was also known as Lewis’

Corps of Light Dragoons or Light

Horse. The unit had about 98 men, nearly half

of whom were sent to various places in Central America.

Jamaica

Rangers emerged in June

1782 from a royal proclamation calling for

the raising of “two

Battalion of free mulattoes and Blacks” as “a means of

removing the Regular Troops to more healthy Stations, by which a

number of very valuable lives may be preserved.” This was the

first ranger unit made up of mulattos and free blacks.

Jamaica

Volunteers, also known as

Royal Jamaica Volunteers, was

raised in Jamaica in October 1779. The unit,

of about 240 men, took part in a campaign aimed at weakening Spanish

power in South America. In 1780 a British amphibious force—whose

ships were commanded by Captain Horatio Nelson, the future hero of

Trafalgar —landed on the coast of today’s Nicaragua and

ascended the San Juan River. During one of the battles of this

disastrous campaign, a Spanish musketball burrowed into Nelson’s

right arm, which had to be amputated. More than a quarter of the

British landing force was killed, wounded, or infected by yellow

fever.

Royal

Batteaux Volunteers, likely the same unit as

the Royal Batteaux Corps, was

raised

in Jamaica sometime in 1779. In February 1780 the unit was sent to

present-day Belize and Nicaragua. Devastated by tropical diseases, in

October 1780 the unit was incorporated into the Jamaica

Volunteers.

James Island Troop

of Light Dragoons, also known as James Island Troop of Horse

This small unit, under

the command of British Army Captain

Alexander Stewart, fought a skirmish against Major

General Nathanael Greene’s Continental Army on August 21, 1781

at Howell’s Ferry, (also known as Russell’s Ferry), South

Carolina. The troops was named after an island that was a

steppingstone to the British capture of Charlestown in 1780.

King’s

American Dragoons

This unit was one of

many Loyalist cavalry units formed to augment the relatively few

British dragoons who served in the war. Raised in 1781, the unit

served briefly in South Carolina and reported killing 40 Rebels in a

battle at Wambaw Creek in February 1782. The commander was Lieutenant

Colonel Benjamin Thompson, whose military career began in

a New Hampshire militia. Prior to raising the unit, Thompson was a

British spy in Boston, using invisible ink to send his messages.

After the war he moved to England, where he became Lord Rumsford, a

noted scientist who established that heat is molecular motion, and

not a fluid.

King’s

American Rangers

On May 1, 1779,

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Rogers, storied commander of Rogers’

Rangers in the French and Indian War, was commissioned by General Sir

Henry Clinton to raise two battalions of Rangers. The 1st battalion

had 133 men. The 2nd battalion, numbering 193 men, was raised by

Rogers’ brother James. Initially recruited in Nova Scotia, the

battalion was garrisoned for a time at Fort St. John’s on the

Richelieu River (now Saint Jean, Quebec).

Robert Rogers mezzotint by Thomas

Hart, 1776

Fort

Ticonderoga Museum

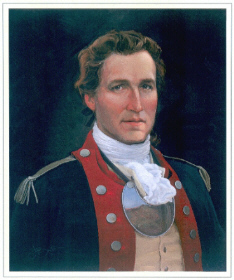

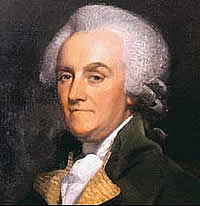

King’s

American Regiment (also known as the 4th American

Regiment)

Raised on Long Island,

New York, this regiment of about 500 men served in New York, Rhode

Island, South Carolina, and Georgia. Members came from the Hudson

River Valley, New York City, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. The

commander, Edmund Fanning, was an aide to William Tryon, royal

governor successively of North Carolina and New York. When Tryon

raided New Haven, Fanning, a graduate of Yale, intervened to save his

alma mater from being destroyed. In gratitude, Yale in 1803 awarded

him an honorary doctorate. After the war, the regiment was placed on

the regular British Establishment, an honor bestowed on only a few

Loyalist units.

|

|

|

|

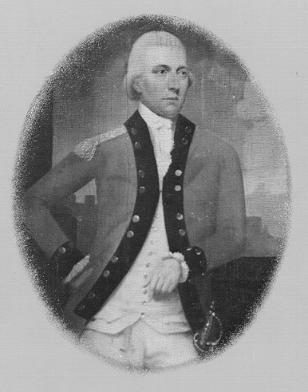

Edmund Fanning

North Carolina

Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries.

|

|

|

King’s

Carolina Rangers (also known as King’s Florida Rangers

and King’s Rangers)

Originally raised in

June 1776 as East Florida Rangers, the unit fought in many

skirmishes defending East Florida. After taking part in the invasion

of Georgia in 1779, the unit was reorganized and named the King’s

Carolina Rangers. Georgia Loyalists later merged with the Rangers.

Evacuated from Savannah in 1782, the unit was transported to

Charlestown. Along with other Loyalist units, the Rangers were sent

to St. Augustine to garrison East Florida. At the end of the war the

unit was sent to Nova Scotia and disbanded.

King’s Loyal

Americans

In 1776, Ebenezer

Jessup, a wealthy Albany Tory, enlisted and outfitted 90 men of this

unit. Hounded by Rebels, he soon took his family to Canada and never

returned to Albany, losing his extensive properties to confiscation.

Also in the corps was his brother Edward. Jessup’s Corps fought

and suffered heavy casualties during Burgoyne’s invasion of New

York in 1777. Survivors went into McAlpin’s Corps and

the Queen’s Loyal Rangers (Peters’ Corps) at St.

John’s, Quebec in 1781. When the unit was disbanded in 1784,

its members settled in Grenville County, Ontario.

King’s

Orange Rangers

The unit was formed in

1776, mainly of men from New Jersey and Orange, New York. Many of

them were tenants on the estates of John Bayard, the prominent

landowner who raised and commanded the unit. Bayard was a Son of

Liberty who turned Tory. Each volunteer was to

“receive 40 shillings advance with new cloaths, arms, and

accoutrements and everything necessary to compleat a gentleman

volunteer.” The Rangers saw action in coastal New Jersey

and New York. When Bayard killed a junior officer in an argument, all

members of his sergeants’ guard deserted and his unit began to

dissolve. Reduced to about 200 men and on verge of mutiny, the unit

was transferred to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in October 1778. Two months

later, one company was transferred to Liverpool, Nova Scotia, to

fight off Rebel privateers and man Liverpool’s Fort Point.

After the war, when the unit was disbanded, many settled in Canada on

land granted for service.

King’s Royal

Regiment of New York, also known as Johnson’s Greens,

Royal Greens, Sir John’s Corps, and King’s Royal

Yorkers.

The regiment was raised

by Sir John Johnson, son of the foremost British Indian agent in

North America. His recruiting began in June 1776 after his escape

from a Rebel force sent to seize him in the Mohawk Valley. Most

recruits were Loyalist refugees from the Mohawk and Schoharie

valleys. The regiment served in Burgoyne’s

1777 campaign in New York, fighting with a force of Loyalists,

Indians, and British soldiers ordered to subdue Rebels in the Mohawk

Valley. At Oriskany, they fought in one of the bloodiest battles of

the Revolution. Driven back to Canada, they later emerged as fierce

raiders who terrified and torched settlements along the New York

frontier, helping the British control land north of the valley. In

1783, the 1st Battalion was disbanded and its veterans settled in

Canada along the St. Lawrence Valley; the following year, the 2nd

Battalion was disbanded and settled in what became Canada’s

Frontenac, Lennox,

and Addington counties.

Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Johnson

Library

and Archives Canada

Loyal American

Association, also known as Loyal Associated Volunteers

Timothy

Ruggles, a veteran of the French and Indian War, became a Loyalist

brigadier general and raised the Association in 1775 in

Marshfield, the only Massachusetts town to oppose the Patriots’

Continental Association. Membership reached about 300. The Loyal

American Association, expected to be the beginning of a

Massachusetts-wide Tory force, was provided British arms and given

protection at first by 100 British troops. On April 20, 1775, a day

after the battles of Concord and Lexington, when a large number of

Patriot militia men threatened Marshfield, the British troops

evacuated the town, along with as many as 200 Loyalists. The 5th

Company of Associators Milita (essentially the same unit as the

Associated Loyalists of Marshfield) assembled in British-occupied

Boston on July 5, 1775 and began patrolling the streets to prevent

all “disorders… by either Signals, Fires, Thieves,

Robers, house breakers or Rioters.”

Loyal American

Rangers

Raised in New York in

1780 from Continental Army prisoners and deserters, along with Tory

refugees, the unit had about 300 men in six companies. They served in

Kingston, Jamaica, and were en route to Pensacola in May 1781 when

word was received of that city’s fall.

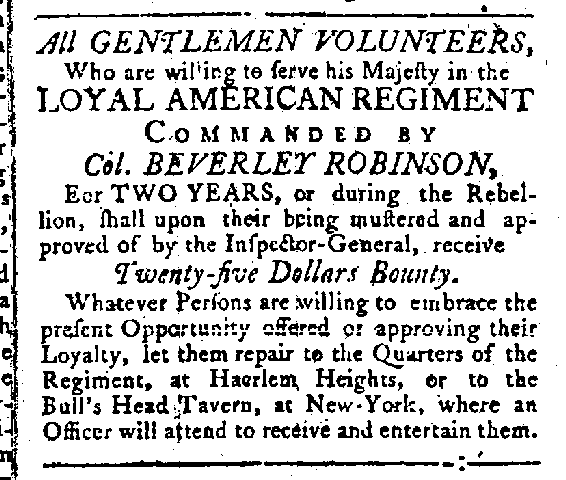

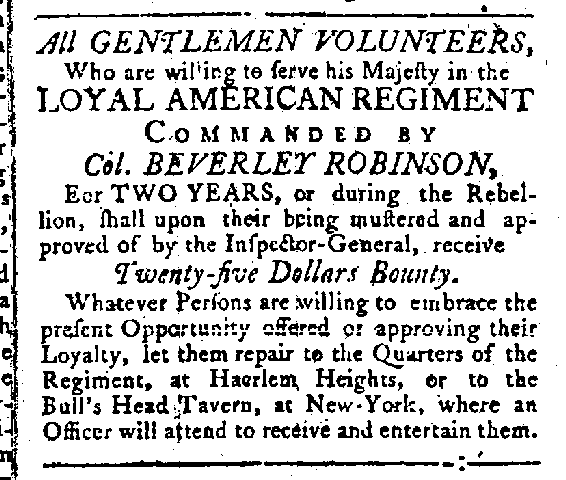

Loyal American

Regiment

Raised in mid-March of

1777 by wealthy Beverley Robinson, the unit consisted almost entirely

of New York loyalists from lower Dutchess and Westchester Counties.

Robinson, a friend of George Washington when both lived in Virginia,

managed 60,000 acres and 146 tenant farms in Dutchess County. His

tenants and their relatives were liberally sprinkled through the

regiment, which he commanded. The regiment fought in battles in New

York and New Jersey through to December 1780, when it embarked for

Virginia under the command of a new British brigadier general,

Benedict Arnold. They later returned to their New York-New Jersey

battlegrounds and joined in a raid on Pleasant Valley, New Jersey,

under Brigadier General Cortland Skinner of the New Jersey

Volunteers. In September 1781, again commanded by Benedict

Arnold, they joined in his terror attack on New London. After

garrison duty in Long Island, they embarked for Nova Scotia in

September 1783.

Beverley Robinson

New

Brunswick (Canada) Museum

Recruiting

Poster for the Loyal American Regiment

Loyal Associated

Refugees

Organized by George

Leonard, a Massachusetts Loyalist, the unit was a sea-going raiding

force of Loyalist sailors and soldiers. In March 1779, joined by a

company of the King’s American Regiment, the unit

raided, but failed to occupy, Bedford (now New Bedford),

Massachusetts. In June 1779 the Refugees became part of the force

that General William Tryon led during his terror raids on Connecticut

coastal towns.

Loyal Foresters

(Forresters)

This unit, which

included Loyalist Indians, was raised to serve with Guy Johnson of

the British Indian Department. The commanding officer was Lieutenant

Colonel John Connolly, a native of Lancaster County,

Pennsylvania. He was captured by Rebels in November 1775 before he

had a chance to carry out his plan to lead a campaign against Rebels

in and around the Falls of the Ohio, where Louisville now stands.

Loyal Irish

Volunteers

James Forrest, an Irish

emigrant from Boston, enlisted Loyalists there in the fall of 1775

and took command. His men wore white cockades in their hats. The unit

was disbanded after the British Army and hundreds of Tories evacuated

the city in March 1776.

Loyal New Englanders

Raised at Newport,

Rhode Island in 1777, under the command of Lieutenant

Colonel George Wightman, the unit served there until the

British Army evacuated the port in October 1779. Next, the New

Englanders became part of the garrison at the Tory stronghold of

Lloyd’s Neck, Long Island. By 1781 there were only about 30 men

in the unit, and they were absorbed into the King’s American

Dragoons and Volunteers of New England.

Loyal Newport

Associators

In 1764 Newport’s

Artillery Company’s guns fired on the Royal Navy warship, HMS

St. John, in New England’s first armed resistance to the

king. A decade later, in December 1776, when the British began their

occupation of Newport, about half of the

company, under Captain (later Brigadier General) John Malbone, joined

the Rebels and the rest joined the Associators and other Tory

units. In 1792, the Rhode Island State Legislature reaffirmed the

unit’s charter, making it the nation’s oldest active

military unit still operating under its original charter.

Loyal Rangers

Formed in 1781, the

unit was created from several smaller companies, including the

Queen’s Loyal Rangers and the King’s Loyal

Americans. Edward Jessup, born in Stamford,

Connecticut, was living in New York in 1759

when he served in the French and Indian War. In 1776, with his

brother Ebenezer and other Loyalists from the area, he joined Sir

John

Johnson’s regiment. Captured while

serving with the King’s Loyal Americans, he was later

released and in 1781 was named commander of the new Loyal Rangers,

which was assigned to raiding parties in New York state and to

garrison duty in southern Quebec.

Loyal Refugee

Volunteers

Abraham Cuyler, a

wealthy landowner and Tory mayor of Albany, New York, raised and

commanded this unit of about 150 men, including runaway slaves

gaining freedom under the British. The Volunteers built a blockhouse

fort at Bull’s Ferry, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from

British-occupied New York City. From that redoubt they raided Rebel

farms in Bergen County, New Jersey, getting supplies and cutting down

trees for wood, which they sold to the British across the river. In

July 1780 the blockhouse successfully warded off a Rebel attack of

about 1,000 men under Continental Army General Anthony Wayne. The

unit later moved to Bergen Point (Bayonne), New Jersey, and to the

site of Fort Lee, where Rebels tried to dislodge them as they began

building a new blockhouse fort there. Finally, the Tories withdrew to

Bergen’s Neck and in the fall of 1782 disbanded. after many

left for Nova Scotia. Other commanders were Major

Thomas Ward and Major Philip Van Alstine.

Loyal Rhode

Islanders

Raised in Newport in

March 1777 under Colonel Edward

Cole, a veteran of the French and Indian War, the unit

was disbanded in November 1777 because of a lack of recruits.

Maryland

Loyalists

The core members of

this 300-man unit were Maryland Tories who fled to British-occupied

Philadelphia. There, in October 1777, the 1st Battalion of Maryland

Loyalists was raised by James Chalmers, a wealthy Eastern Shore

planter. When the British Army evacuated the city in June 1778, the

Marylanders also left and fought in the battle of Monmouth. First

sent to Halifax, they later served in Jamaica and Pensacola, capital

of the British West Florida colony. Captured when Pensacola fell to

the Spanish, they were paroled to New York City. By the end of the

war, small pox and desertions had shrunk the battalion to about 100

men. They, along with their wives and children, sailed to Canada,

where they had been granted land. Their ship, HMS Martha, ran

aground in the Bay of Fundy and sank. Most men drowned, but many

wives and children survived.

Maryland Royal

Retaliators

Nearly 1,300 Loyalists

swore oaths to join this corps, raised by Marylanders Hugh Kelly and

James Fleming, mainly in Pennsylvania. The Retaliators had ambitious

plans to recruit as many as 4,000 men for a campaign to aid the

British in the taking of a large swath of Pennsylvania and Maryland.

But Rebels learned of the plan, arrested Kelly and some 170 men;

three were convicted of treason against Maryland and hanged. Fleming

and others escaped to join British forces in North Carolina. After

the British surrender at Yorktown, both men made their way to

British-occupied New York. Kelly was later reported living in Nova

Scotia.

McAdam’s

Independent Company of Volunteers

Far more is known about

John Loudon McAdam than about the Loyalists he recruited in New York

for his Company of Volunteers. Born in Scotland, he sailed to New

York as a youth and lived with his uncle in New York City. During the

Revolutionary War, he was the commissioner for prizes ships captured

by the Royal Navy and British privateers. He offered more than 450

ships for auction, collecting fees for those he sold. Those fees

provided some of the basis for his fortune when he moved back to

Scotland, bought land, got involved in local road-building, invented

a new paving process—and gave the world “macadamized”

roads. As for his Volunteers, little is known; they were among the

countless Loyalists who were recruited in Tory Town, as New York City

was called.

John Loudon McAdam

McAlpin’s

Corps of Royalists

When General John

Burgoyne invaded New York from Canada, among his forces were Loyalist

volunteers, including McAlpin’s Corps, commanded by Major

Daniel McAlpin. After serving 40 years in the British Army, McAlpin

had retired in New York. In 1774 he bought about 1,000 acres on the

west side of Saratoga Lake and became a prosperous farmer. After

Rebels seized his property, he became a soldier again. He received a

warrant from General Sir

William Howe, secretly raised a unit of about 180 men and

officers, and marched off with Burgoyne. After the battle of

Freeman’s Farm, some of his men were drafted into British

regiments that had suffered heavy casualties. Loyalist survivors of

the Burgoyne expedition were placed in the King’s Royal

Regiment. In May1779, McAlpin’s own surviving men were

returned to him. They were mostly assigned to garrison duty and

fortification construction in Quebec Province. Although seriously

ill, McAlpin continued in command until he died in July 1780.

Negroe Volunteers

This unit was raised in

Savannah during the 1779 siege of that British-held city by a joint

American-French force. The black Loyalists, unlike ex-slaves given

menial Army chores elsewhere, the Negroe Volunteers were used as

soldiers armed to fight the besiegers. One of the two armed companies

was commanded by Captain Hartwel Pantecost (who would later become an

officer in the James Island Light Dragoons); the other by

Captain John McKenzie of the British Legion. The unit was

probably disbanded by the end of the year. The British remained in

control of Savannah until July 1782.

Newfoundland

Regiment, also known as His Majesty’s Newfoundland

Regiment of Foot

In September 1780

British authorities authorized the raising of a force of 300 men to

defend the colony. Many were recruited from the recently disbanded

Newfoundland Volunteers; others may have been drafted from the

Artificiers and Labourers, since that unit and the

Newfoundland Regiment were both commanded by Robert

Pringle, a major by 1780. The regiment was garrisoned in

and around St. John’s until the end of the war.

Newfoundland

Volunteers, also known as Royal Newfoundland Volunteers

In 1778 Captain Robert

Pringle, an officer in

the Royal Corps of Engineers, was authorized to form the Volunteers,

the first recorded military force to bear the name “Newfoundland.”

Its members were mainly civilian construction workers employed by the

British Army. They built a military road and worked on Fort Townsend

at St. John’s. The unit was disbanded the following year in a

dispute over the paying bounties.

New Hampshire

Volunteers (also known as Stark’s Corps)

In spite of its name,

this unit was raised in New York City and Philadelphia by William

Stark of New Hampshire, who had commanded a company of Rogers’

Rangers during the French

and War. William Stark was the older

brother of Rebel General John Stark, the hero of the Battle

of Bennington. Stark, originally a Rebel

became dissatisfied with the way he was treated. So he went to

British-occupied New York and offered his military services. His unit

was raised in the spring of 1777 but seems to have been soon

disbanded, with its men being absorbed into the Queen’s

American Rangers in New Jersey. Later, would-be recruits wound up

in the 2nd battalion of the New Jersey Volunteers and the

King’s Orange Rangers. Several officers joined the

Guides & Pioneers.

New

Jersey Loyalist Military Units

Cortland Skinner, the last attorney

general under the Royal government of New Jersey, was commissioned a

brigadier general by British authorities in September 1776 and

empowered to raise a brigade of six battalions to be known as the New

Jersey Volunteers. (Royal Governor William

Franklin also made Skinner a major general

of militia.) Skinner did raise his battalions by December 1776, and

he provided them with green uniforms, a color that came to be

associated with armed Tories. But, because none of the battalions

reached their authorized strength, the brigade was eventually reduced

from six battalions to four. The Continental Army, during victorious

battles at Trenton and Princeton, captured several of Skinner’s

commissioned officers, including one who had documents showing that

he was attempting to raise an Irish battalion for Skinner.

New

Jersey Militia. Sketchy accounts indicate

that 50 to 60 militia men from Monmouth County crossed to

British-held Staten Island in June 1776, bringing their personal

arms, “a stand of colours,” and not much else. With his

headquarters at New Brunswick during the British occupation there,

Skinner reorganized the Monmouth

County Militia, under

his commission as major general of militia, striving to make the

militia able to prevent “small parties [of Rebels] from

entering the County, and distressing the People.”

New

Jersey Volunteers, also known as Skinner’s

Greens. When

Skinner was given his commission, the 1st

battalion of this corps was already forming, with many more Loyalists

only awaiting the arrival of British troops in New Jersey before

joining them as Tory allies.

1st

battalion of New

Jersey Volunteers, established

on July 1, 1776, served as garrison troops at Richmond, Staten

Island, while training. They entered New Jersey in December 1776 as

part of a force pursuing Washington during his retreat from Fort Lee.

Several hundred more recruits were raised in Monmouth County. In

January 1777 the battalion formed part of the British garrison at New

Brunswick and in June 1777 returned to Staten Island, its station for

the next five years.

2nd

battalion of New

Jersey Volunteers was

established in

November 1776 by Lieutenant Colonel John

Morris, a retired lieutenant of the British Army’s 47th

Regiment of Foot. On January 2, 1777 four soldiers of the unit were

killed in battle and as many as 30 others captured during the battle

at Monmouth Court House. The battalion also fought in smaller

actions. In April 1777, ordered to New York, the unit was assigned to

service with the Royal Artillery Regiment, recruiting Rebel deserters

to fill it ranks. The unit guarded woodcutters and ships. When it was

broken up, men were drafted into the 1st and 4th battalions.

3rd

Battalion of New

Jersey Volunteers was established in November

1776. Its first commander, Edward

Vaughan Dongen, was mortally wounded in a battle with a large Rebel

force retaliating against Tory raids. Members

of the battalion were notorious raiders throughout 1777. In December

1778 they sailed to Georgia, where they joined British troops who

took Savannah. Through 1779 and into 1780, the unit served in

Georgia. When the unit’s light company was ambushed at

Musgrove’s Mills, every officer was wounded and many men were

killed or wounded. Other companies staged raids out of their garrison

at the town of Ninety Six. Some men of the Volunteers

of Ireland, a disbanded regiment, were

brought into battalion. In January 1783 the unit returned to Long

Island, losing many as deserters. At the end of the war, the

remaining men and their families sailed to Nova Scotia, where the

unit received a grant of land.

4th Battalion of New Jersey Volunteers

was established in the fall of 1776

by Bergen County surgeon Abraham Van Buskirk. The unit consisted of

ten companies of varying strength. Members conducted raids against

Rebel homes and fighters in Bergen County and garrisoned parts of

Bergen Neck and Staten Island. In the summer of 1779 the battalion

moved into nearby Paulus Hook, now Jersey City. A contingent serving

with the American Volunteers

landed in Georgia in February 1780 and advanced northward to link up

with other British troops near Charlestown. Back north, a

reorganization brought companies of the 4th Battalions (also the 1st

and 2nd) and several other units into the Provincial

Light Infantry, which joined an expedition

that sailed for Virginia in October of 1780. On February 27, 1781 a

party of 20 men from the 4th held off ten times their number until

arrival of the rest of the unit. On September 8, 1781 the battalion

was part of the British force that defeated General Nathanael Greene

at Eutaw Springs, South Carolina. In September 1783 the unit embarked

for Nova Scotia.

5th

Battalion of New Jersey Volunteers of about

250 officers and men from

Sussex County was raised

by Joseph Barton in November 1776. Early in 1777, the unit went on

raids for a while before taking on garrison duty on Staten Island.

The battalion saw little more battle action before it was disbanded,

its men being transferred to a reorganized 1st battalion.

6th

Battalion of New Jersey Volunteers was raised

in December 1776 by Isaac Allen, a Trenton

lawyer. The men came from the Hunterdon County area, including

Trenton and Princeton. Washington’s attack on these places

slowed down recruiting and cost the battalion two officers. After a

battle in February 1777, in which several men were killed and about

60 taken prisoner, the battalion set up quarters on Staten Island.

Undersized to start with and with ranks depleted, the battalion was

merged into the 3rd Battalion.

West

Jersey Volunteers were

raised in Philadelphia in January 1778 and served primarily in and

around Billingsport, New Jersey, until the evacuation of Philadelphia

in June 1778. Because it was an under-strength regiment, its men were

drafted mainly into the 1st and 3rd battalions of the New

Jersey Volunteers and the British

Legion.

New

York Loyalist Military Units

After

the British conquest of New York City and Long Island in 1776,

Loyalists chose the occupied territory as their new home. Prominent

Loyalists, such as leaders of the DeLancey and Robinson families,

quickly raised regiments. Many Tories, who called themselvesRefugees,

began arriving from the neighboring area, from Pennsylvania, and even

from the South. Many royal militias became Loyalist military units.

The American Volunteers, while

serving as a detached corps from the British Army, trained New

York militias.

DeLancey’s

Brigade also

known as the New

York Loyalists,

was probably the largest armed Tory organization in New York. The

brigade—three battalions of 500 men each—was raised by

Oliver DeLancey, a wealthy New York merchant who resided in the

Morrisania section of the Bronx (then part of Westchester County).

Some of the men in the 3rd battalion were said to be Rebels captured

during the battle of Long Island and given a choice: Join the

Loyalists or rot in a prison hulk in New York harbor. At first,

members of DeLancey’s Brigade served as a police force in New

York City. Later, they garrisoned forts at

Kings Bridge and on the north shore of Long Island, where they often

were accused of ill-treating Loyalist civilians. The 1st and 2nd

battalions served in East Florida, then in Savannah. So many men were

killed in battles there and in South Carolina—at Eutaw Springs

and during the siege of Fort Ninety-Six—that the two battalions

were merged in February 1782. Battalion

commanders included Lieutenant Colonel John Harris Cruger, Colonel

George Brewerton, Lieutenant Colonel Stephen DeLancey, Major Thomas

Bowden, and Colonel Gabriel G. Ludlow. He became the first mayor of

Saint John, the destination of many of the Loyalists who sailed to

Canada after the war.

Loyal

Volunteers of the City of New York was under

the command of David Mathews, royal mayor of New

York City. Locke’s Independent

Companies, raised in New

York by Joshua

Locke in

1779

was

probably included among the Volunteers, as was the Mayor’s

Independent Company of Volunteers.

Mathews and his followers were

involved in a conspiracy known as the Hickey Plot, a complex

conspiracy aimed at infiltrating and subverting the defenses of New

York and kidnapping or assassinating George Washington. Mathews,

placed in house arrest in Litchfield, Connecticut, escaped and

returned to New York, where he resumed his office under the British

occupation. Shortly before British troops evacuated the city in

November 1783, Mathews sailed to Nova Scotia.

Nassau

Blues, raised in May

1779, was disbanded in December of the same year, when most members

then joined the New York Volunteers.

William Axtell was supposed to raise 500 men from the Nassau, New

York area, but he was said to have only raised about 30 men.

Jamaica-born William Axtell was heir to a large New Jersey estate

when he arrived in America in 1746. He married Margaret De Peyster,

daughter of Abraham de Peyster, Jr., and through her mother, a Van

Cortlandt—two of the wealthiest Loyalist families of the era. A

member of the Governor's Council in 1776, Axtell was commissioned a

colonel and given command of the Blues, known to foes as the “Nasty

Blues” because of reports of torture chambers in at Axtell’s

palatial Brooklyn mansion, Melrose Hall. Rebels confiscated Melrose

Hall, which was purchased after the war by a Continental Army officer

who had married Axtell’s adopted daughter.

New

York Volunteers were sent

to East Florida in October 1778 and helped to defend Savannah in

September 1779. After battles in Charleston, Camden, and Hobkirk’s

Hill, South Carolina, they returned to New York in August 1782. The

unit was disbanded in Canada in 1783. Units in

the Volunteers were also known as the New York

Companies, the 3rd

American Regiment, and the

1st Dutchess County Company,

which became the 3rd Regiment.

King’s

County Militia was commanded by Colonel

William Axtell, who had had little success

raising the Nassau Blues. He

did better with this militia, whose muster in

November 1777 showed seven companies of infantry, 25 sergeants, 26

officers, 7 drummers, 337 rank and file (the usual military term for

ordinary soldiers), and a troop of light horse with 5 officers, 3

sergeants, and 32 rank and file. The unit had a religious tinge:

Officers signed a “Declaration Against Popery,” denying

the doctrine of transubstantiation and objecting to idolatry.

New

York Rangers (also known as the

First

Independent Company of Rangers, was

commanded by Christopher

Benson whose recruits were from New York City and Long Island. The

Rangers, part of the New York City

garrison, dealt with parolees and prisons and performed other

military police duties. In August 1777 the Rangers arrested Colonel

Ethan Allen at a tavern in New Lots, Long Island, for violating his

parole.

Queen's

County Militia troops assisted Associated

Loyalists in repelling and attempted landing

at the Tory stronghold of Lloyd’s Neck, Long Island, by a force

about 450 troops, most of them French.

Richmond

County Militia was commanded by Colonel

Christopher Billopp of Staten Island. He was twice captured by

Rebels, who despised him for his militia’s raids in Staten

Island and New Jersey. On his first confinement

in 1779 he was chained to the floor and fed only bread and water in

retaliation for the harsh treatment of two Rebel prisoners.

Taken ill while a prisoner a second time, he was, with General

Washington's permission, put into more comfortable quarters and then

sent home. Billopp’s brother, Thomas, was in a Rebel militia.

Suffolk

County Militia was commanded by Colonel

Richard Floyd, owner of a 500-acre farm in

Brookhaven (now Mastic), Long Island. The Floyd family had inhabited

Long Island since 1654. Richard Floyd shared an ancestor with William

Floyd, a major general in the Rebel militia and a signer of the

Declaration of Independence.

Westchester

County Militia, commanded by

Colonel

James DeLancey, appears

to be same unit as DeLancey’s Refugees,

also known as the Westchester Light Horse, the

Westchester Chasseurs,

and DeLancey’s Cow-boys.

Westchester militia men skirmished with Rebel troops throughout the

war and earned a reputation as harsh raiders. The unit reportedly

grew from about 60 to upwards of 500. Members were not paid or

supplied—and made it a rule never to come back from a raid

empty-handed.

James DeLancey

Early

Manhattan Island

Westchester

Chasseurs were feared

in New York’s Westchester County as “DeLancey’s

Cow-boys”—a name inspired by the Chasseurs’cattle

rustling. They specialized in raiding

small villages and looting unarmed Rebels. A typical raid was

reported in the pro-Tory New York Gazette

on October 16, 1777: “Last Sunday Colonel James DeLancey, with

sixty of his Westchester Light Horse went from Kingsbridge to the

White Plains, where they took from the rebels, 44 barrels of flour,

and two ox teams, near 100 head of black cattle, and 300 fat sheep

and hogs.” General George Washington, in a report on the

Chasseurs, wrote in a report to Congress on May 17, 1781: “Surprise

near Croton River by 60 Horse and 200 Foot under Colonel James

DeLancey ... 44 killed, wounded and missing ... attempted to cut him

off but he got away.”.

DeLancey sailed for England in June